Summer 2022 Newsletter

Presbyterians and the First State University

In 1789, North Carolina became the first state to authorize the establishment of a public university funded at least in part by the state. In 1793 the author of that law, William Richardson Davie and other trustees laid the cornerstone of the first building, now known as Old East. Students arrived in 1795, and UNC was the only state university to grant degrees in the eighteenth century.

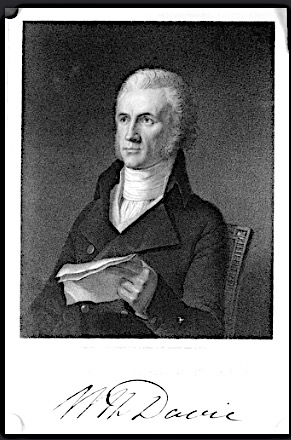

Engraving of William R. Davie is from the State Archives of North Carolina

However, the pressure for a university had begun even before the American Revolution, and it came largely from Presbyterian leaders in the province. It was an article of faith for Presbyterians that all clergy should have studied the scriptures in Greek and Latin and should have a university degree or its equivalent. Some of the early Presbyterian ministers in North Carolina had studied in Scotland or Northern Ireland, others in northern universities, many at the College of New Jersey, a Scots-Irish institution that later became Princeton University. Some who supplied church pulpits were licensed to preach but not yet ordained. The shortage of ministers was keen. When Orange Presbytery was established in 1770, it included all 35 established churches in North Carolina and only seven ministers. Synods encouraged ministers to begin classical academies at their churches, and some did, to prepare students for academic training at university. But they really wanted higher education to be available in North Carolina.

In 1770 the colonial Assembly passed an act to create Queen’s College in the town of Charlotte. It was ratified by Governor Tryon in 1771, primarily to please the Presbyterians who had assisted him against the Regulators. The college president was to be Edmund Fanning, close friend of Governor Tryon, and the Board of Trustees consisted of one member of the established Church of England and four Presbyterians. Fanning was too busy suppressing the Regulators to take the post, but the college apparently was open in Charlotte in 1771 and 1772, without final approval from the king.

When the Commissioners for Trade and Plantations in London finally reviewed the law in 1772, they recommended it be disallowed by the king, since it would essentially be run by dissidents, namely Presbyterians. Word that the charter for a college was not approved arrived in 1773. A school continued for a while as the Queen’s Museum and then as Liberty Hall Academy.

After the Revolution and the ratification of the Constitution, leaders were able to return again to the lack of higher education available within the state. The first proposal for such an institution was submitted to the Assembly in 1784 by the Rev. Samuel E. McCorkle, minister at Thyatira Presbyterian Church and president of Salisbury Academy. The Assembly rejected that proposal but accepted one submitted in 1789 by William Richardson Davie. Davie, though probably a Deist, had been raised by his Presbyterian minister uncle in the Waxhaw area and had graduated from Princeton in 1776. These two were the principal founders of the new university. Davie helped choose the location and recruit faculty; McCorkle chaired the committee that planned the course of instruction. In 1793 Davie laid the cornerstone of the university building and McCorkle delivered the address.

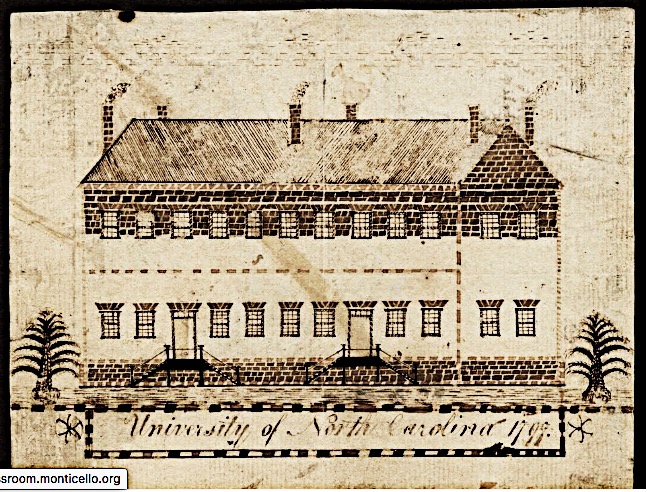

When constructed in 1793, Old East was the first state-funded university building in the United States. Sketch of Old East made by student John Pettigrew in 1797 is from the North Carolina Collection, UNC-CH Library, as is the photo of the Old Well.

The university officially opened in January 1795, and the only faculty member, David Ker, was given the title of presiding professor. The following year he was forced to resign as he had given up his Presbyterian faith. Charles Harris, a Presbyterian and graduate of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, was the next presiding professor and professor of mathematics. In 1796 he asked Joseph Caldwell to replace him as professor of mathematics, and the following year Caldwell became the presiding professor as well. Licensed to preach but not ordained, Caldwell taught at the university until his death in 1835. When the office of president was created in 1807, he was elected by unanimous vote of the trustees. His contributions to the university were enormous. In 1811 the state had withdrawn support, and Caldwell raised $12,000 for completion of the South Building where most classes were taught. A noted astronomer, he helped survey the southern boundary of North Carolina, traveled to Europe to purchase telescopes and other equipment for the students, and personally paid for building an observatory on campus in 1830, the first constructed for educational purposes in the U.S. His writings also championed improved transportation and public education.

The antebellum university continued to rely primarily on well-educated ministers to teach its classes, as part of the university’s mission was to instill piety and discipline. Although other denominations often objected, most of the faculty were Presbyterian, including David Swain, Elisha Mitchell, and James and Charles Phillips.

Student drinking from the bucket of the Old Well, c.1892. In 1897 President Edwin Alderman, whose office looked out at the well, decided to replace the wooden structure with a classic design and add a little beauty to the grim, austere dignity of the old campus.

Historic Hillsborough Presbyterian Church

Hillsborough Presbyterian Church is a contender for the oldest continually used church in North Carolina. It was built in 1814 to replace the Church of England/Episcopal building that had been destroyed by fire. As there was no other church in the town, the space was promised to whichever denomination secured a minister first. The Rev. John Knox Witherspoon agreed to come, and the Presbyterian congregation was organized by Orange Presbytery in 1816. Witherspoon was the grandson of the Rev. John Witherspoon of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) who had signed the Declaration of Independence. John Knox Witherspoon was twenty-five when he became pastor of the new church and principal of the Hillsborough Academy. His half-brother Frederick Nash, who later became the Chief Justice of North Carolina’s Supreme Court, is buried near him in the Old Town Cemetery next to the church.

The Burwell School is now a historic site

The following minister, the Rev. Robert Burwell with his wife Margaret, began a school for girls in their home from 1837 to 1857.

The lot the church was built on, though not this church, is quite important in the history of North Carolina. The Church of England structure was the site of the Third Provincial Congress of 1775 and the meeting place of the N.C. legislature in 1778, 1782, and 1783. The first statewide convention called to ratify the federal Constitution of 1787 met here in 1788 and refused to ratify it until a Bill of Rights was included.

Hillsborough Presbyterian Church, 102 West Tryon St., Hillsborough

The town was an important political and cultural center in the 18th and 19th centuries. A walk through the Historic District of the town will take you past beautiful homes, the restored Colonial Inn, and the antebellum courthouse, still in use. The Orange Co. Museum is around the corner from the church. There also is a beautiful riverwalk along the Eno. East of town is Ayr Mount (1815), the plantation home of the Scotsman William Kirkland.

Spring Tour of Historic Churches: Granville and Vance Counties

Our spring tour began at the Oxford Presbyterian Church, where Sam Martin presented Pastor Alan Koenke with a certificate noting the church’s bicentennial celebration in 2018. Sam also presented him with the book on Presbyterian history in North Carolina by Harold Dudley, published by the Society. Pastor Koenke then led the group in prayer. Lindsey Moore, a member of the church, shared its history, beginning with the family of Thomas Blount Littlejohn. They gave the land for the church in Grassy Creek, the mother church of Oxford Presbyterian. Littlejohn’s parents were prominent residents of Edenton, where his father ran a shipyard and his grandmother was the first woman lawyer in NC. When their daughter turned 13, Littlejohn and his wife started an academy for girls. During the pastorate of Rev. Joseph Labaree in the early 1800s, membership of the young church, which included slaves, grew steadily. Our time at Oxford Presbyterian ended with Kathy Webb, organist, playing the Casavant organ.

From the church we drove to the George C. Shaw Museum, which houses artifacts and memorabilia from the days of the Rev. Dr. Shaw and the Mary Potter Academy. We heard from two women who are members of the Mary Potter Club, and who attended the Academy, which closed in 1971. The difference that academy made to students of color is a story not enough people know. The graduates are devoted to keeping the history alive. It was hopeful hearing how Presbyterians worked to see that people of color received an education.

Hostess Rosalyn Green with museum volunteers and tour members

Joining us at the Museum was Rev. Dr. Omotolokun Omokunde, the current pastor at Timothy Darling Presbyterian Church, where the Mary Potter Academy began. During our visit to the Timothy Darling Church, Dr. O. gave us an entertaining and enlightening talk about the history and the continuing work of the church in the community. His wife Dawn Marie, who is very active with Presbyterian women across the General Assembly, talked about the extensive work of Presbyterian women in the state and in the nation.

Dr. and Mrs. Omokunde

We rode by the Grassy Creek Church on our way to Nutbush Presbyterian Church, which some of us remember from summer camps and church retreats at Presbyterian Point. We had lunch at the church and heard the history of the church and the area from Rev. David Vellenga, former pastor of the church. Rev. Henry Pattillo (1726-1801) was one of the most well known pastors at Nutbush; he was active in the Revolution, started an academy, and published the first textbook in NC. An historical marker stands in tribute to him along the nearby highway.

St. John’s Episcopal Church (Photo from Our State Magazine, Jan. 31, 2022)

The tour ended at St. John’s Episcopal Church, the oldest wooden Episcopal church in NC (1772). It is an interesting structure that speaks to the culture of the time with enclosed pews, a high pulpit, and separate spaces for persons of color.